*Nicolae Țîbrigan

The moment of Prince Vladimir I in Red Square

Source: cdn.rbth.com

In December, of 2016, the modern Russian cinematography of Russia was being enriched with another production, falling under the category of “patriotic movies” – the historical and patriotic movie “Viking,” (Викинг – n.r.), directed by Andrei Kravchuk — with a budget of 20.8 million dollars. Partially financed by the Russian government, the production was one of the three most expensive movies in the post-Soviet era of the national movie industry — after the two episodes of the movie “Burned by the Sun 2,” directed by Nikita Mihalkov. The movie is based on medieval chronicles of the Russian Prince Vladimir I, or Volodimir I (also named the Holy and the Mighty), who, with the help of Vikings from the Scandinavian peninsula, managed to conquer Kievian Russia ruled by his brother Yaropolk. Everything seems fine up to this point; however, according to some historians and movie critics, the filmmaker has allowed some inaccuracies and outright false information about some events in the early Middle Ages, i.e., the 10th century. Taking into consideration the way the movie has been intensely promoted on state-controlled channels, we can only make an educated guess about the true intentions of the initiators of this cinematic project. Even the Russian president appreciated the movie; given that, in 2014, he declared that the act of Christianizing of Prince Vladimir in Crimea signified the importance of the region for Russia’s national identity, although neither Moscow nor Russia existed at that time. Moreover, let’s not forget that Ukraine, as well as Belarus, view the Kievian Russia as part of their own cultural and historical heritage.

This last movie production — along with the documentaries “Crimea – The Road Towards the Nation” (Крым. Путь на Родину – rus.) and “The President” (Президент – n.r.) — represents idealized archetypes of the newly “constructed propaganda,” with narratives and methods adapted for the 21st century, which Russia uses as a soft-power instrument with medium- and long-term consequences.

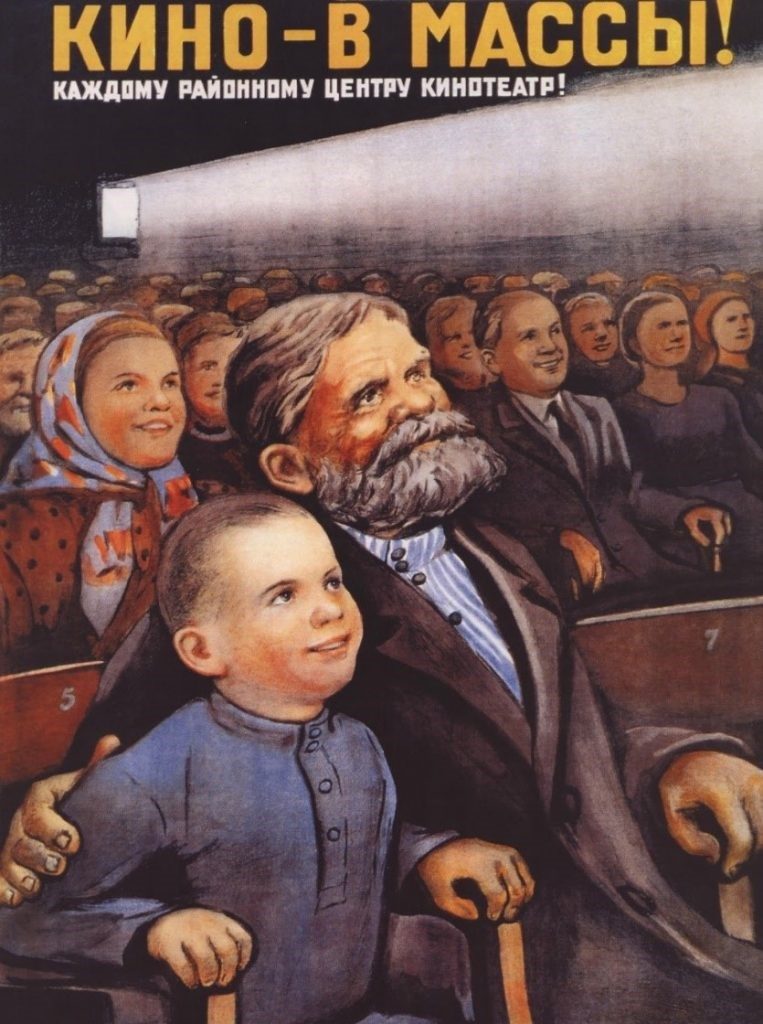

Soviet propaganda banner “Movies for the people! A cinema for each district center”

Source: soviet-union-posters.blogspot.ro

As the current Soviet leadership, Putin, and Putin’s Russia, have used movies as a propaganda tool to stimulate a revenge-like nationalism and to influence Western public opinion in favor of the mindset that promotes the inexistence of Ukrainian statehood, especially given the movies’ efficient and impressive distribution throughout the world – in more than 60 countries. Let’s not forget that, not long ago, movies were used in the Soviet Union for propagandistic goals, and the falsification and mystification of history represented specific techniques typical to any communist regime. From the birth of the RSFSR (November 7, 1917), the Bolshevik leaders sustained that the art of movies could represent an ideal propaganda tool for spreading abroad the ideals of the Socialist Revolution, and Lenin saw movies as the primary means for the quick and efficient education of the proletariat. The idea was upheld afterward by Joseph Stalin, who was amazed by the success enjoyed by Hitler in his political ascension with the help of the radio and cinema.

Like the dictators of the 20th century, today’s Russia exploits on a sizeable cultural scale, that includes the art of film, to propagate its state ideology and distribute, to other countries, the narratives with which the Kremlin agrees. “The patriotic movie” puts history and factual data through a blender, mixing images, special effects, constructed narratives, stunts, a lot of blood, myths, historical falsehoods, passions, and emotions. In such a context, movie propaganda is more efficient, and the first victims are people sensible to messages that are overwhelmingly emotional, without much critical thinking. Moreover, the narratives could influence perceptions and attitudes of the target public on specific subjects of history, politics and inter-human relationships. Thus, I recommend at least accessing Wikipedia or browsing historical studies before watching a Russian “patriotic” movie or documentary.

In other words, Romania and Moldova were not favorite subjects of Russian “patriotic movies,” but some productions have managed to induce or insinuate the public perception and stereotypes of Romanians. You see examples from “Brother 2”, where a secondary persona does not distinguish between Romanians and Bulgarians, characterizing them all as feminized; the Romanian Army not participating in the Pleven attack in “The Turkish Gambit”; or the Romanian peasants from the SSRM with gratitude towards the Soviet liberators in the face of “Brejnex”; the jokes about the Romanian army by the Russian ambassador, Kuzmin; or even the “contribution” of the Russian Embassy in the reinterpretation of the Romanian history. All of these have contributed to the construction of an alternative reality, parallel and even contradictory, about Romanians living in the two nations, worthy only of a Radio Yerevan joke. Such movies, documentaries and publicity stunts play the role of genuine “misinformation sounding boxes” and manipulation of the subconscious – accentuated dangers, due to their simple accessibility in the online realm, where broadcasting exceeds the legal limit most times, thus breaking copyright norms.

Still, following the logic of Mao Zedong’s quote at the start of the movie – “History is the symptom, and the diagnosis is us” – the filmmaker, the historian, and the propaganda designer all meet to falsify “the symptoms,” for the “malady” not to be detected. From now on, neither the truth nor the lie matters, but rather, the perceptions based on the emotions of fascination and doubt, picked from the images and dialogues of the “patriotic film.”

* Nicolae Ţibrigan holds a BA in Sociology at the University of Bucharest, a graduate of the Master of Security Studies at the Faculty of Sociology and Social Work, University of Bucharest. He is currently enrolled at the Doctoral School of the same faculty with the title “The Gagauz Colonists from Bessarabia after the Great Union.” He has experience in the field of European projects, participating in numerous volunteer initiatives both in the Republic of Moldova and Romania. Starting with 2013, he is an expert at the Black Sea University Foundation (FUMN) and a research assistant at the Institute of Political Science and International Relations “Ion I.C. Bratianu “of the Romanian Academy.